Before Julian Assange founded Wikileaks, a groundbreaking effort was made by Daniel Ellsberg in releasing the Pentagon Papers, which revealed forbidden truths about the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons.

Time Stamps:

Opening (0:00)

Little Old Ladies and SOBs (3:57)

A Special Spy Ring Project (8:44)

The Fatal Flaw of No Questions Asked (14:49)

The Scope of Death and Destruction (19:46)

Little Old Ladies and SOBs

Daniel Ellsberg hoped that by exposing damning top secret information, he could persuade President Richard Nixon to end the Vietnam War, as the previous administration would suffer the bulk of the embarrassment. Instead, out concern for the office of the presidency, Nixon's administration created the Special Investigations Unit, aiming to “plug” the leaks and destroy the reputation of those who would dare to publicize them.

On July 17, 1971, Egil “Bud” Krogh was summoned to a closed-door meeting by John Ehrlichman, who gave him responsibility for conducting the Special Investigations Unit, later known as “The Plumbers.”

Following the leak of top secret government documents, including the Pentagon Papers, the Plumbers were formed to “investigate.” To “investigate” in this Nixonian context meant circumventing the role of the courts, the FBI, and the Justice Department. The SIU - “the Plumbers Unit” - would report to John Ehrlichman, and their activities would remain as top secret as once were the documents themselves.

The leaks made Nixon furious, and the New York Times Company v. United States decision that affirmed the right to publish them put him at war with the law itself. To Nixon, this was a national security crisis, and such “treason” was not to be tolerated. He needed a national security task force, and “a real [SOB] to take it by the horns. One whose sense of loyalty and toughness would far outweigh his regard for “legal niceties.”

This disqualified Attorney General John Mitchell, who was known for his concern for the “technically correct,” and White House Counsel John Dean, who was viewed by senior staff as a “little old lady.” The Kroughs have given notably more favorable treatment to Dean than the authors cited in our coverage of Watergate. Dean is credited with urging Ehrlichman to call off the break-in at the Brookings Institution, which may explain his reputation for a time as not nearly aggressive enough for the Plumbers Unit.

Krogh pondered endlessly as to why he qualified as an ideal choice. Why not Chuck Colson? Why not G. Gordon Liddy? Both of them could “play political hardball” and appealed to Nixon's dark side. Accounts less charitable to Dean highlight his willingness to cast aside ethical considerations, but also, to rat out co-conspirators to avoid facing consequences for his own actions.

Even towards the end of his life, Bud Krogh remained perplexed as to why Nixon chose him to co-direct the Special Investigations Unit.

As he addressed in The White House Plumbers:

So why did I get the assignment? l speculate that I can hardly have been the first choice. Nixon had wanted a black ops kind of guy, a "real [SOB]." I was the very thing he said he didn't want, a "kid," and quite interested in the "technically correct” myself...

Even though I don't think I fit the dark profile the president wanted for the job, perhaps a simpler reason l got it was that it was understood that I would do it to the best of my ability and not ask questions. At that point in my White House career, I wasn't given to lengthy reflection on whether I was competent or experienced enough to do the jobs assigned to me. I certainly wasn't in the habit of questioning the orders or wisdom of my superiors, Ehrlichman and Nixon, to whom I gave complete loyalty.

A Special Spy Ring Project

Then-GOP Minority Leader and eventual President Gerald Ford helped Liddy land a job in the Nixon Administration. E. Howard Hunt was brought into the unit by Chuck Colson. Hunt had a long career with the CIA and at least two false retirements. While Hunt claimed he was not officially with “the Agency” at the time, he retained connections that might prove useful to the Plumbers. Krogh observed that Hunt “could blend easily into any group without drawing undue attention.”

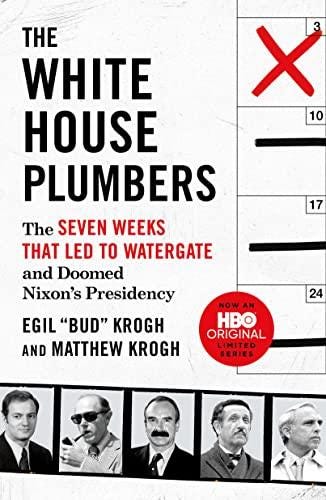

As described in the product description of The White House Plumbers:

Driven by blind loyalty, diligence, and dedication, Krogh, along with his co-director, David Young, set out to handle the job, eventually hiring G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt, who would lead the break-in to the office of Dr. Fielding, a psychiatrist treating Daniel Ellsberg, the man they suspected was doing the leaking. Krogh had no idea that his decisions would soon lead to one of the most famous conspiracies in presidential history and the demise of the Nixon administration.

Daniel Ellsberg undoubtedly shared the conclusion that the break-in of psychiatrist Lewis Fielding's office marked “the beginning of the end” for the Nixon Administration.

Had my lawyers and I known about the break-in from the beginning, [John] Ehrlichman would have had to shut down the illegal plumbers operation, and the Watergate break-in of June 1972 might never have taken place.

While short-sighted research into the matter failed to conclude that Ellsberg's file was ever obtained, Ellsberg himself disagreed, citing material he had written for the American Political Science Association, which alluded to the Pentagon Papers. That only Hunt's team was to be “directly involved” in the break-in at Fielding's office suggests that the CIA may have gotten Ellsberg's file and kept its various contents out of the hands of the Nixon Administration. Some of it, however, was conspicuously left at the scene of the crime.

According to Henry Kissinger, Ellsberg was “the most dangerous man in America.” In a rush to judgment, Nixon considered him a traitor, and suspected he may have an allegiance to the Soviet Union.

New York Times columnist R.W. Apple Jr. observed:

"Though the Pentagon Papers dealt with a foreign war, they taught a lesson applicable to domestic politics as well: It is almost always better, once trouble breaks, to get out all the damaging evidence at once, rather than stonewalling and allowing it to trickle into the public domain, thus creating the impression of an ever-mounting crisis. It is a lesson mostly unlearned.

Why? Partly the natural impulse for self-protection, partly the deep-seated governmental belief that the public should not be allowed to watch the sloppy business of policy-making because it would not understand and partly the conviction that the policy makers know best and mean well."

Apple had taken part in exposing the “Five O'Clock Follies” - a derisive term for military briefings that members of the press considered unreliable - in his pointed lines of questioning.

H.D.S. Greenway explains:

It wasn’t that the American briefers were actually lying to us. They were, as the journalist Sebastian Junger wrote about American optimism in Afghanistan, simply inviting you to join a conspiracy of wishful thinking.

The question that should follow is obvious: How can policy-makers make sensible decisions when the public is subjected to false impressions and the “conspiracy of wishful thinking” fed to them by the military-industrial complex?

Unaware of the break-in - casually titled "Hunt/Liddy Special Project No. 1" in John Ehrlichman's notes - Daniel Ellsberg potentially faced a maximum sentence of 115 years, in a trial conducted by an unsympathetic judge. As the Watergate scandal came to light, revelations of this “special project,” which forced Judge Byrne's hand through gross governmental misconduct and illegal intelligence gathering, and gave way to Ellsberg's exoneration.

The Fatal Flaw of No Questions Asked

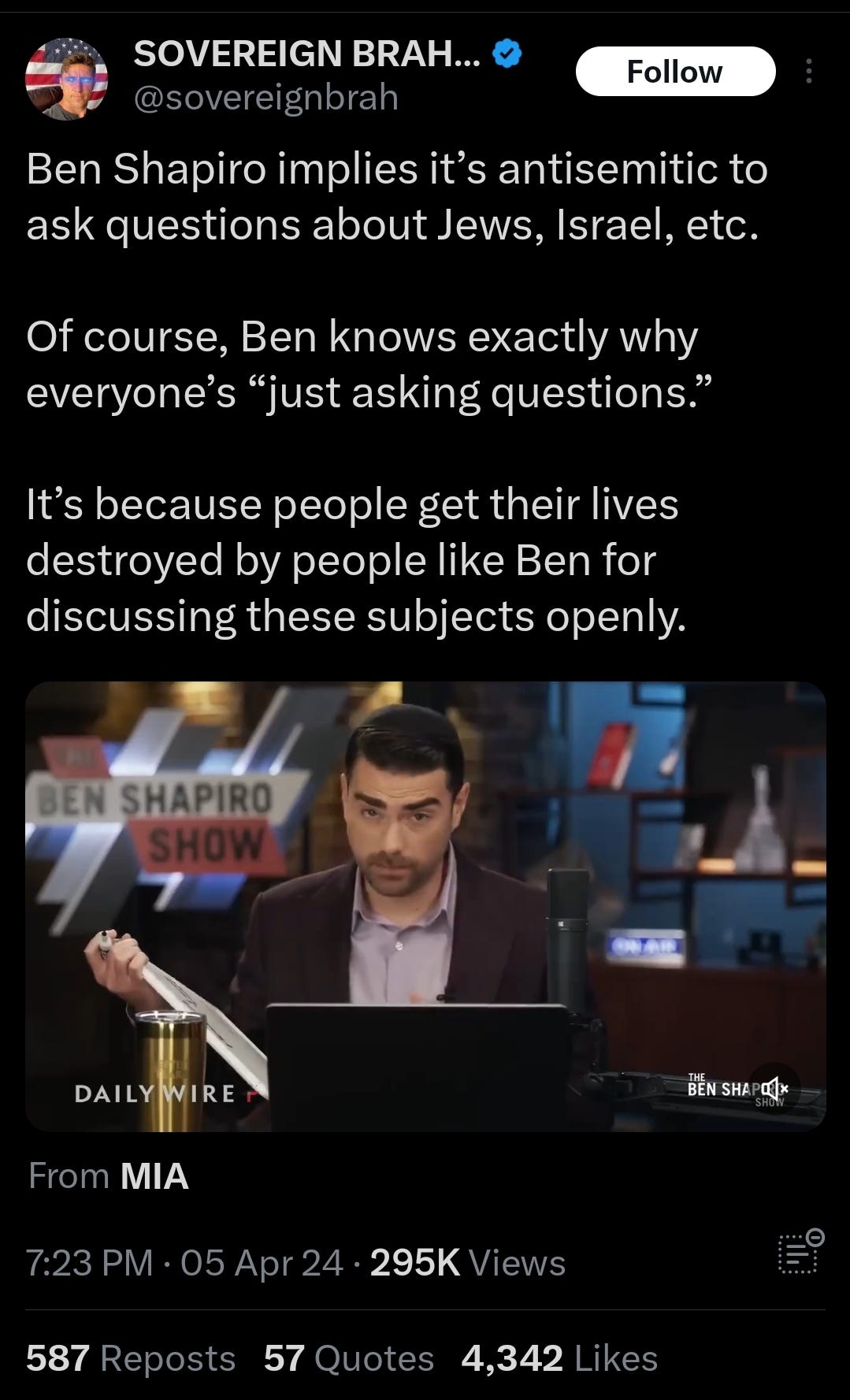

In recent memory, the phrase “just asking questions” has been viewed as a red flag against a line of inquiry that demonstrates a refusal to operate within a set of established perimeters, and instead, leads an audience down a rabbit hole to embrace a conspiratorial cynicism.

This view was perhaps most vividly on display by Ben Shapiro of the Daily Wire, expressing his exasperation with other political commentators in their coverage of Israel's attacks on Gaza.

You blame society [that] you don't have an answer, so it must be conspiracy… This is the game that is played by so many corrupt commentators “just asking questions.”

I don't have to show you evidence that something terrible is happening. I don't have to actually demonstrate how the thing is happening. I don't have to tell you who the problem is, wink wink.

But I can just tell you right now that there is [something going on] and if I'm asked about it, “hey, I'm just asking questions.” Now, let me tell you something, not just asking questions… is a game for children. My son is seven, he can “just ask questions.” My daughter is ten. She can “just ask questions.”

If you're 50 and you're “just asking questions,” I don't think you're just asking questions. I think that your level of curiosity is actually quite low. I think that you don't care enough to know or know enough to care. I think that the vast majority of people who are in the “just asking questions” business have an answer that they want to suggest, but they know there's no evidence for it. So instead, they hide behind “just asking questions.” In other words, they're completely full of sh*t.

As pointed as this rant may be, let us suppose it may apply to some in the business of political analysis. We might call it a bad application for a conspiratorial approach, since it involves an answer without much supporting evidence. Timing is “always suspect,” and coincidental factors may properly raise more questions than answers.

But to reverse the implication of “just asking questions” is to suggest that “no questions asked” has a stronger foundation. Such was the tone of Nikki Haley on sending aid to Israel.

If the production of knowledge is largely built upon questions to obtain answers, one wonders what could possibly substitute the role of inquiry.

Are some questions more “allowable” than others?

Who decides, and on what basis?

If the process of inquiry begins to shatter the sacred Overton Window, is it best to bleach the inquiry out of existence?

What if people in power have motives that we need to know about?

By now, it should be obvious that there's a fatal flaw at a certain point in embracing the extremes of “no questions asked.” The arbitrary line for “allowable” and “unallowable” inquiries also represents a hindrance for the production and revelation of knowledge, albeit one of degree. It seems that motive is ultimately the best judge, but that may be left to guesswork. As to say, determined by the assumptions of the listener, which are so often flawed to begin with.

Perhaps wading through such a gray area is a matter of faith. The good along with the bad, in whom and what. But of all things, asserting a benevolent actor against a malevolent one in the fog of war leads to a blind eye when the former resorts to an expedient measure, as the assertion is to be defended at all costs. This leaves Mr. No Questions Asked to hide behind that mantra, even if “there's no evidence for it.”

The realm of undue absolutes quickly forces one to hide behind a twisted sense of loyalty.

It is here we must further investigate the account of Egil “Bud” Krogh, the co-director of Richard Nixon's infamous White House Plumbers Unit.

The Scope of Death and Destruction

Following the first Plumbers meeting in Room 16 of the White House, the FBI and the CIA assessed that a full leak of the Pentagon Papers had reached the Soviet embassy before the New York Times had published them. “[R]aw and unconfirmed as it was,” tells Krogh, “I was confident that we all agreed that Ellsberg was very likely at the center of a Soviet-sponsored conspiracy to diminish U.S. influence in the critical theater of Vietnam.” The next leak (SALT I) only intensified this notion, along with the efforts to plug the leaks.

Felipe de Diego, Bernard Barker, and Eugenio Martinez were contacted by Hunt to participate in a national security operation, which appealed to their sense of patriotism.

On the Friday evening of September 3, the operation was carried out. The intruders inflicted damage intended to give the appearance of a drug burglary. Liddy had called Krogh to confirm a clean break, but claimed not to have obtained information on Ellsberg.

The plan, which called for a “covert operation,” had been documented in Polaroid pictures of damage intending to make the break-in less traceable to the White House, and more akin to a drug burglary. Both Krogh and Ehrlichman were appalled by the damage done, and shut down any further investigation of Ellsberg, as it had already gone well beyond the scope of what either of them had envisioned.

When Liddy was questioned about a combat knife he carried during the operation, he told Krogh (who had little to no experience in covert operations) that he would have killed if necessary to protect himself and the team if they felt threatened. For Krogh, it was a shocking admission.

Nixon was informed the next day about a “little operation in California” that yielded nothing, and it was best that he knew nothing further about it.

This foreshadowed the story of Watergate, as Nixon seemed to set the stage for an “investigative group” adopting lawless means, however desirable the ends may have been, while making his exit into oblivion once those seeds were planted. An “investigative group” with a familiar cast of characters, with varying degrees of loyalty.

Following Liddy's departure from the Plumbers Unit to join the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP), a leak appeared in a piece by Jack Anderson that originated from within the National Security Council staff. Bud Krogh was relieved of any further participation with the Plumbers Unit when he disagreed with a wiretapping operation, leaving David Young to carry out an intrusive investigation that produced a “massive report” that remains unavailable to the public to this day.

While Krogh had no knowledge of the Watergate break-in prior to a front page story in the St. Louis Dispatch, he correctly suspected Liddy as its mastermind, and Jeb MacGruder approving it. Tasked with handling the cover-up, John Dean had advised Krogh to suppress any information that linked Watergate with the White House.

US Attorney Earl Silbert assigned his assistant to conduct interviews on various White House staff. The activities of the Plumbers Unit were to be bound by a secrecy requirement, and to avoid answering questions pertaining to national security. Dean did not consider the Fielding break-in relevant to Watergate, and encouraged the Plumbers to deflect accordingly.

Krogh was asked of any knowledge he may have had about travel by Hunt and Liddy to California in 1971, which he dodged away at the time. The question was prompted by a photograph left in the camera by Liddy and Hunt that was obtained by the CIA, and sent to the Department of Justice.

While Krogh saw Dean stuck with a “thankless task” and no real involvement in Watergate, the Nixon tapes reveal Dean stating that Watergate started as "an instruction to me from Bob Haldeman." Dean would deny this for many years, and find himself cast unfavorably by revisionist accounts of Watergate that detail his involvement. These accounts suggest that Dean advanced in the ranks and achieved “real [SOB]” status in his ambition and commitment to opposition research. And driven by that ambition, he metastasized the “cancer on the presidency.”

Diego, Barker, and Martinez eventually faced prosecution for taking part in the break-in at Fielding's office, and dozens Nixon's own men would end up paying a price between the Fielding break-in and the Watergate scandal.

But if the Nixon Administration ultimately gained nothing but eventual exposure for corrupt and criminal conduct, why didn't they change course?

How did Nixon figure that he could win a deeply unpopular war “in honor?”

Why was the decision made to “protect the presidency” with increasingly secretive and lawless behavior when the Pentagon Papers revealed information that would have primarily damaged his predecessor and his party?

Why wouldn't an administration that spoke of “law and order” seek to exemplify this creed in its own conduct, and regard the rights of its citizens as sacred and inviolable?

In the end, “protecting the presidency” cost Nixon his job, his reputation, and his legacy.

See Also:

External Resources:

The White House Plumbers: The Seven Weeks That Led to Watergate and Doomed Nixon's Presidency by Egil "Bud" Krogh and Matthew Krogh

Memo to Bush White House staff by Egil "Bud" Krough

Meet the White House Plumbers by Laura Dail and Matthew Krogh

25 Years Later; Lessons From the Pentagon Papers by R. W. Apple Jr.

What I Saw in Vietnam by H.D.S. Greenway

The World’s Most Famous Filing Cabinet by Owen Edwards

Ehrlichman is Convicted of Plot and Perjury in Ellsberg Break-In; Liddy and 2 Others Also Guilty by Linda Charlton

Cuban Says He and Two Others Broke Into Psychiatrist's Office by the New York Times

John Dean Slams "Revisionists" and Nixon Foundation in Talk at Library by NixonTapes.Org

Egil Krogh tells his story in "Integrity" by Chuck Leddy

Leaning on Journalists and Targeting Sources, for 50 Years by David E. Sanger

Donate to Mr. Menger:

Tip with Buy Me a Coffee

Tip with Cash App