The Hoppean view on public property being "owned by the taxpayers" necessarily requires embracing a sovereign people as a concept. Privatization in action demands the abolition of cancel culture.

Time Stamps:

Intro/Tipshow Announcement (0:00)

Taxpayer Ownership Requires a Sovereign People (1:15)

Homesteading and the Lockean Proviso (5:39)

Privatization Demands the Abolition of Cancel Culture (6:59)

Memes to Mayhem: Conquering the Digital World With Our Souls Intact (8:30)

Mixing Labor With Webspace (13:15)

Taxpayer Ownership Requires a Sovereign People

The Hoppean take (in reference to political philosopher Hans-Hermann Hoppe) on public property being "owned by the taxpayers" necessarily requires embracing a sovereign people as a concept.

This isn't reconcilible with corporate monarchy, which seemingly divorces political authority and representation. If a public road is "owned by the taxpayers," a "practical Jeffersonian" approach necessarily follows with regard to the present system.

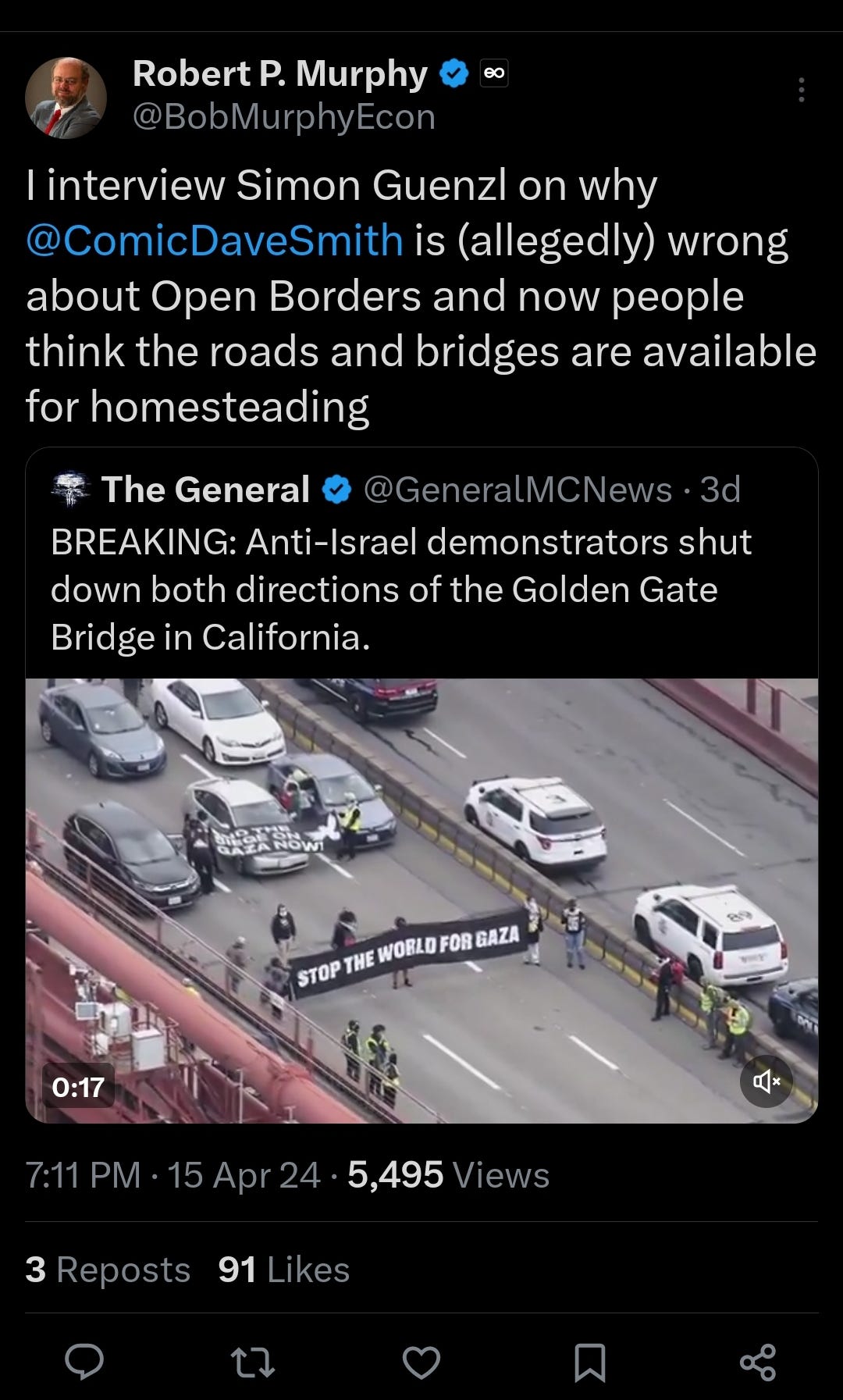

This also comes to blows with the view that public property can be homesteaded by original appropriation. There's no way for theory to be justly realized. Its absurdity is perhaps best demonstrated by protesters blocking the flow of traffic.

The problems with democracy that Hoppe identifies are minimized when they're in the form of a local referendum. The difference, I suppose, is that the posterity incentive is in the hands of voters, instead of a hereditary line.

Homesteading and the Lockean Proviso

In his 1690 work, The Second Treatise of Government, Enlightenment philosopher John Locke advocated the Lockean Proviso which allows for homesteading.

For Locke, the mixing of labour with land is the legitimate source of its ownership:

Though the earth and all inferior creatures be common to all men, yet every man has a property in his own person. This nobody has any right to but himself. The labour of his body and the work of his hands, we may say, are [likewise] properly his. Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state that Nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with it, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property.

Furthermore, Locke held that individuals have a right to homestead private property from nature only so long as "there is enough, and as good, left in common for others.” In other words, the Lockean Proviso requires that appropriation of unowned resources must regard the rights of others and cannot make anyone else worse-off.

Privatization Demands the Abolition of Cancel Culture

It's clear that the public is made worse off when they cannot reach their destination by using a public road - which they've paid for- and find themselves... Jammed. Forestalled. Entrapped. The injustice this situation creates is undeniable.

But even leaving aside the "worse off" qualifier, the Lockean Proviso deals with that which is taken out of its state of nature. The soil which has not been mixed with human labor. Territorial virginity.

This is not the case with a public road, already made of human labor. We can say it wasn't a legitimate action. Fair. But we cannot play the tape in reverse and make anyone whole. We certainly can't entrap the public away from their jobs, their families, and their lives, as all depend on the function of access that has been established. Where would they go?

Instead, the road can be privatized with a tax dividend paid back to the tax base. Once privately-owned and operated, the importance of culture is all the more clear.

You cannot have a functional private property system in a pervasive climate of cancel culture. If you do, vast portions of the population are at risk with the same problems as presented with a spontaneous act of protest, blocking the road for attention.

It is here that we take a rather sharp exit onto the metaphorical superhighway, the Internet.

Memes to Mayhem: Conquering the Digital World With Our Souls Intact

A lot has unfolded since the advent of widespread Internet access. The prospects of a digital profile spark the imagination and free us from the constraints of stressful face to face interaction. We may even assume a pseudonymous identity that allows us to escape ourselves.

We may also “go pseudo” as a buffer against the threat of doxxing, a phenomenon where strangers seek to damage your reputation and any way they can. If you're not Sean Hannity, you probably work a day job. Maybe your employer can hear the most outlandish tale ever told about who you supposedly are when you're dealing with such a troublemaker.

Does he hate you, your digital persona, or perhaps both? Does their digital persona hate you, and has it conquered what may otherwise have been a decent person on a different path?

Netflix recently released The Antisocial Network: Memes to Mayhem, a documentary focused on the intersection between internet culture and real-world politics.

Viewers are guided through a chain of developments…

From 2Chan to 4Chan

4Chan to Anonymous

Anonymous to Occupy

Occupy to Qanon

That all serve as an outgrowth from one another.

A central figure in this story is Aubrey Cottle (also known as Kirtaner or Kirt), who was central to the creation of Anonymous, which grew out of 4Chan.

Anonymous would adopt a form of activism that unleashed a trolling culture onto the streets. A group of clever agitators known both for their hacking abilities and the iconic Guy Fawkes masks put fear into their targets.

Their anonymity and knack for “hacktivism” proved a temptation in walking the line. The sense of empowerment. The ego trip. The upper hand in mastering a modern “life hack” in the art of deception.

Just as the line between internet culture and reality had been tested.

As 4Chan founder Christopher Poole (aka “moot”) would find, the original vision would be superceded by the will of its member participants who seemed to view any lines drawn as not only an undesirable suggestion, but an attack on their personalities - albeit, digital personalities - which nevertheless served as their primary vessels of expression.

This was equally true of Anonymous.

In a movement without a leader or a gatekeeper who commanded respect, no lines could be drawn regarding who to hack, who to threaten, or how to handle the information obtained, legally or not.

It is here that we concede Curtis Yarvin's argument against decentralization in its most extreme form. That is to say, we cannot identify the single person responsible, hold them accountable, and correct the wrong done with any level of satisfaction.

Mixing Labor With Webspace

Is there a digitized version of the Lockean proviso?

When one mixes their digital labor with open webspace, for example, does he have a claim to its contents? Does his claim “die” once he contracts with an institutional distributor - a “platform” - or are there terms properly assumed when not explicitly stated in the agreement?

If the content creator can be held legally liable for unlawful speech, what does he retain on the other side of the equation? Does he forfeit the contents of speech that is protected, but retain it when it is libelous or threatening?

Should certain considerations override the sovereignty of a platform that's a state-chartered corporation, with artificial personhood, that enjoys multi-billion dollar government subsidies, that profits from the sale of metadata, but ultimately serves as a digital town square?

The Section 230 privisions of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 would seem most sensible if the service providers involved couldn't flip the switch of designation between publisher and platform.

The word “platform” doesn't appear in the law, but the phrase “information content provider” served the designation. The courts have adopted the term “platform” without altering the relevant provisions in any obvious way.

How often would a free society even need to entertain these questions? As Ron Paul said, “[l]iberty is not complicated.” Not if the people are sovereign and their institutions are constrained.

See Also:

External Resources:

Gaza protest shuts down Golden Gate Bridge for hours, causing gridlock on both sides of span by Dave Pehling

Golden Gate Bridge protesters released without charges by Pat McMahon

Seattle's CHAZ: Homesteaders or Illegal Squatters? by Jeff Deist

Second Treatise of Government by John Locke

Publisher or Platform? It Doesn't Matter. by David Greene

Donate to Mr. Menger:

Tip with Buy Me a Coffee

Tip with Cash App

Share this post